Some Debt Is Not Like the Other

With all the talk lately concerning the U.S. debt and how it will grow due to the new tax plan, we thought it would be a good idea to address what it means. First and foremost, we must differentiate between individual/corporate debt and the debt of a sovereign nation such as the U.S.

Individual and corporate debt must be managed in a fiscally prudent manner or face devastating consequences for themselves and their companies. If individuals overextend themselves by racking up credit card debt or buying a house they can’t afford, there are mechanisms in place to rectify the situation by banks repossessing the collateral. Similarly, if corporations overextend their leverage, the bankruptcy lawyers can put the corporations out of business and sell off assets to recoup some of the losses. However, national debt is a whole different situation. In fact, I sometimes wonder why the word debt is used to describe loans from the U.S. government because the meaning is so different than what we consider to be traditional debt.

From a definition standpoint, national debt is similar to individual/corporate debt in that one party is borrowing money from another party and agrees to pay periodic interest throughout the term of the loan and then principal at maturity. This is where the similarities end. U.S. Treasuries, unlike other debt, never needs to be paid off. When the U.S. runs out of the ability to pay its current liabilities, they simply issue additional debt to pay off existing debt. There is no mechanism in place to repose or foreclose on government assets and the cost to borrow more debt stays relatively stable.

A more appropriate measure of national debt would be how the U.S. compares to other nations and what percentage of GDP their debt accounts for. According to the International Monetary Fund, global debt accumulated worldwide has exceeded $63 trillion. Although the U.S. is only a small portion of the land size and population of the world, we account for close to one-third of the worldwide debt with $20 trillion. Obviously, this is concerning but it may not be as bad as once thought.

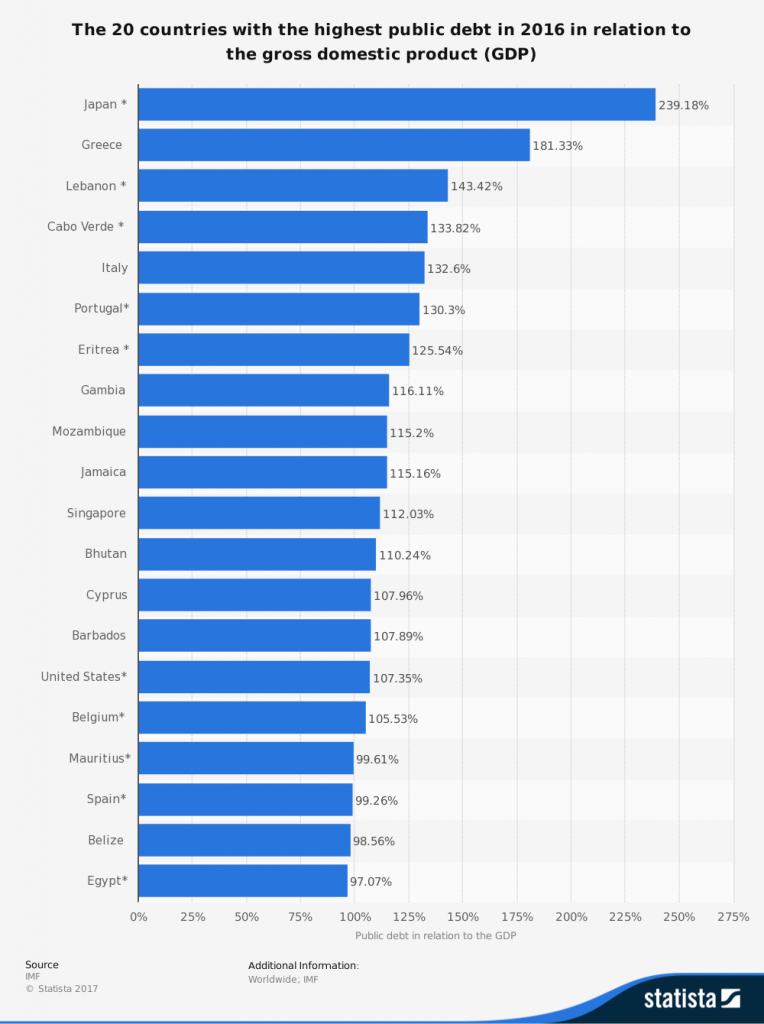

For a perspective on what this means, we need to look at what percentage of GDP a nation’s debt accounts for. Since GDP represents the dollar value of all goods and services produced, it is a good measuring stick to gauge the overall health of an economy. The ratio used is a percentage of debt to GDP with 100 percent being equal to one year of GDP.

For example, as the graph below shows, current U.S. debt is approximately $20 trillion with the percent to GDP at 107 percent. Japan, at second place as far as dollars issued has $11.8 trillion but its percent to GDP is an astounding 239 percent. This is currently the highest debt to GDP ratio in the world and is the result of decades of mismanaged fiscal and monetary policy. Unfortunately, not only did Japan not stop their continued debt issuance, but they doubled down time after time with no real progress in improving the situation. Hopefully the U.S. policy makers can see the errors made by Japan and not follow the same path.

Right behind Japan in debt to GDP is Greece with $353 billion in debt but with a debt ratio of 182 percent of Greece’s GDP. Unlike the U.S. though, and to some extent Japan, Greece doesn’t have the economy to produce enough to lower their ratio. Greece has been in the news constantly the last few years for their inability to pay their debt and has had the E.U. to either forgive or “loan” them money to pay their debt. The ability for Greece to issue more debt on their own is non-existent.

What this all means is that although $20 trillion in debt is not optimal, the U.S. can still weather this because we have the ability to grow our economy and produce goods and services to honor our commitments. Lowering the outflows of fixed or variable cost is often not mentioned in D.C. but at some point, we will have to address this part of the income statement as well to make sure our debt service is not too high.

Sources: IMF, Visual Capitalist, Statista